Essays Shaun Scott — April 15, 2015 13:32 — 0 Comments

One Day in the City of the Future – Shaun Scott

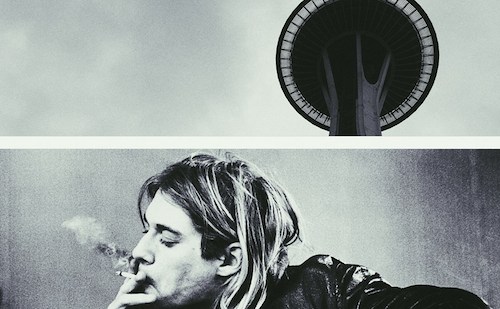

Slight by skyscraper standards, Seattle’s Space Needle stands 605 feet near the eastern shore of Elliot Bay: two-thirds as tall as the Eiffel Tower, and no match for the 1776-foot Freedom Tower built in the wake of the terrorist attacks of September 11th, 2001. But the building has cut a formidable figure as a civic symbol since its construction in 1962.

The Space Needle has been celebrated: its alabaster color appears pristine when plastered on broadcasts of Monday Night Football, in Macklemore’s music videos, in the critically acclaimed films of Seattle-based directors Megan Griffiths and Lynn Shelton. And it has been the subject of ridicule: an over-the-top vignette titled “Skinless in Seattle†from a 1995 episode of The Simpsons shows the structure tipping over into the bloodied eye of a cartoon cat. Rival fans who hate the Seahawks are quick to point out that the totem of a town which hosts the professional football team with the most PED-related suspensions since 2011 happens to resemble an intravenous syringe.

Through it all, the Space Needle stands sort of tall. If, as Goethe said, “architecture is frozen musicâ€, then the Space Needle remains the signature song of a city that reared Ray Charles and killed Kurt Cobain: a golden oldie sent from the 60s, a feel-good favorite recorded on analog media by city fathers who anticipated an Information Age the city eventually became synonymous with. Designed to resemble a flying saucer placed atop a David Lemon sculpture called “The Feminine Oneâ€, no other building better represents the sky-high ambitions of an outwardly progressive city with so much to prove.

Tucked in the northwest corner of the nation, Seattle is a city that loves looking at itself in the great mirror of American spectacle. It would be absurd to say that Kanye West “put Chicago on the map†or that Woody Allen “made people notice New York City,†but practically every export in every generation from Seattle has had something like this said about it. When you realize just how important the lust for recognition is in the city’s cultural libido, you may start to read it between the lines of all the city’s headline achievements these last few years: in Macklemore’s infamous amplification of his private text exchange with Kendrick Lamar after the Grammy Awards in 2014, in the boasts of the Seattle Seahawks’ secondary, in the over-achieving local film scene which has been disproportionately represented at international film festivals like Sundance.

If you can make it in New York, you can make it anywhere—but many find that making it in Seattle means making it elsewhere: and to do that, you have to make yourself visible. But what is a picture worth?

In 1959, Seattle businessman Joe Gandy had an answer. He was a key figure of the committee that traveled to the Bureau of International Expositions (BIE) in Paris that year, hoping to get permission for the Seattle World’s Fair that would eventually result in the erection of the Space Needle. At the opening pitch session in Paris, Gandy literally had to show the French where Seattle was on a map. Part of his committee’s presentation involved addressing concerns that a World’s Fair in Seattle would come with the same labor strife as the Depression-riddled New York World’s Fair in 1939. After all: the French might not have known where exactly Seattle was, but the General Strike launched there in 1919 was still an inspiration to beleaguered laborers everywhere.

To bolster Seattle’s case before the BIE, Gandy obtained an agreement from all unions representing workers at the World’s Fair—including construction workers who built the Space Needle—that there would be absolutely no strikes for the duration of the civic celebration. Several Seattle-area unions also donated dues to the fair’s cause, and encouraged ordinary citizens to volunteer their labor to city beautification projects that would impress visitors.

The space-themed Century 21 Exposition opened on April 21st, ran for 6 months until mid-October, and was a smash success. It attracted 10 million visitors, and it turned a profit. Walt Disney and Bobby Kennedy used it is a photo op. Elvis Presley shot a film on the Space Needle. What is a picture worth?

Ask Abby Lawlor. She’s a strategist for Unite Here! Local 8, the union that represents hospitality workers at the Space Needle—today, in 2015, 53 years after the Space Needle first opened. From where I sit and talk with her at a café near her office at the Labor Temple on 1st Avenue, the landmark is visible. “Coming from Miami, I guess I did have the expectation that Seattle was this progressive place,†Abby tells me, as I do my best to uphold civic stereotypes by eating a giant bowl of granola. “But I’ve seen that that isn’t really the case.â€

Since 2011, workers represented by Abby’s union have been engaged in a labor dispute with the Space Needle. She tells me that some workers at the Space Needle make as little as $11 an hour, that the average wage for Space Needle workers is somewhere between $14 and $15, and that the labor force there has received just one raise in nearly five years—a bump of 35 cents an hour in 2013. To put these numbers in perspective, The Puget Sound Business Journal reported in August of 2014 that two adults with two school-age children would both need to pull down $22.07 an hour in Seattle’s King County to make a living wage. The number expands to $24.06 in a household with a single adult and one school-age child. It balloons to $34.46 where there’s a single adult with two children. Though Seattle recently passed a citywide minimum wage of $15 per hour, laborers who work for large employers like the Space Needle won’t have their salaries increase until 2017—by which time, the rising cost of living which was an impetus for the $15/hour minimum wage in the first place will likely rise further. Meanwhile, Washington has the most regressive tax code in the union, meaning that lower-income residents there pay a greater share of their income in taxes than they would if they lived in any of the other 49 states.

In this context, it should come as no surprise that management at the Space Needle made news in early 2015 when it circulated a webinar called “How To Live On Less†to its workers when they formally requested a raise. Local press outlets KIRO 7 and The Stranger jumped on the news, casting it unfavorably as a condescending move by a callous company. Abby says that when press asked officials at the Space Needle about the contents of the webinar, “they let it slip that they didn’t produce it, and that it was made by some HR firm.†The firm is nicknamed “Shags†after its owner Steven Shagrin, who lists “money coaching and financial literacy education†as his specialties on LinkedIn. His “How To Live On Less†presentation includes advice such as “avoid feeling deprivedâ€, “be creativeâ€, and “Make It Fun!â€

In the thick of his company’s dispute with Local 8 in 2013, Space Needle CEO Ron Sevart launched a PR campaign to help protect views of the Space Needle. Sevart aimed to rezone the bustling South Lake Union neighborhood in order to restrict buildings there from reaching a certain height. While locked in an internal struggle over his employees’ wages, Sevart still wanted to preserve the landmark’s “photographic integrity.†What is a picture worth?

America watched the Seattle Seahawks lose Super Bowl XLIX to the New England Patriots in stunning fashion on Sunday, February 1st, 2015. The morning after, news hit of a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) ruling that revealed upper management at the Space Needle was guilty of encouraging its employees to resign from the union. The NLRB found that the Space Needle turned its back on a written commitment to deduct union dues from the pay of its workers. The Space Needle attempted to poll its employees to determine who may or may not be sympathetic to the union. The Space Needle even laid off two seasonal employees for joining Local 8. Declaring the Space Needle’s actions illegal, the NLRB ordered the Space Needle to cease and desist its anti-union tactics, to rehire the laid-off workers, and to pay withheld back dues to Local 8.

Abby says that, in recent weeks, this story has receded somewhat from the civic conversation. Space Needle management has remained deftly silent about its labor dispute with Local 8. “They’ll try to say that they negotiated with us,†sighs Abby, “but it was clear to everyone that the last deal they put on the table really wasn’t satisfactory at all. So here we are.â€

Prior to sitting down with Abby, I was familiar with some of the details of this labor dispute. But having the facts explained in person on this typically overcast day made the story seem like a parable about the price of visibility for structures of power. In his 2009 text Capitalist Realism, Mark Fisher describes the importance of symbolic achievements in 1930s Soviet Russia: to deflect attention from the pitfalls of life in a failed state, Stalin planned grand public works projects. The dictator trotted out picturesque but practically useless canals, and stately-looking bridges that couldn’t actually bear any weight. For Fisher, “late-capitalism in America repeats Stalinism’s [way of valuing] symbols of achievement over actual achievement.†Seen in this light—the light of critical reflection—the Space Needle’s self-important stature and subtly rusting paint job suddenly seem faded and sad.

The Century 21 Exposition’s monorail still runs its piddling 1-mile route from the Space Needle to the heart of downtown Seattle, but the city is frequently wracked by debilitating traffic jams because of its historical inability to muster resources for city-wide rapid transit. As my conversation with Abby concludes, I find myself thinking about how I’ll be getting to my next appointment over in Ballard. But like a well-prepared prospect looking to leave a good impression at the end of a job interview, Abby seizes the opportunity to ask whether I think there is anything Local 8 could be doing to make the story of the Space Needle’s workers “more visible.†It’s a question I find deeply ironic—what could be “more visible†than the Space Needle?

I tell Abby that I thought her union’s use of social networking websites was extremely effective. On its Facebook page, Local 8 occasionally posts testimonies of what a raise could mean for employees at the Space Needle. One morning while wasting time on Facebook, I see a stirring post by a valet cashier named Veronica Chernichenko. “If we get a raise,†it begins, “I will be able to finish college. I will be able to move closer to the city and save time and money on my commute. I will be able to help my parents get back on their feet while my dad is recovering from illness. But more than that,†Veronica concludes, “my coworkers who have dedicated their lives to the Space Needle will be rewarded for their hard work.â€

When I introduce myself to Veronica on Facebook and say I’m interested in writing about her personal story with the Space Needle’s labor dispute, she suggests we conduct our interview “520 feet off the ground!†in the Space Needle’s observation deck.

I don’t refuse.

I want to talk to Veronica because it seems to me her story represents the other Seattle—the Seattle behind the glitz of the new Amazon campus, behind the digital gloss of our high-tech reputation. The Seattle whose mayor, Ed Murray, took campaign contributions from the utility company Comcast, and who coincidentally refuses to take action towards forming a municipally owned digital utility. The Seattle that takes its very name from a Duwamish tribal chief, but where the Duwamish Tribe has yet to achieve federal tribal recognition. A cynical Seattle. A city so jaded by wealth stratification and police brutality that local luminaries Sherman Alexie and Ijeoma Oluo took to Twitter after the Super Bowl to say that Marshawn Lynch didn’t get the ball on the 1-yard line because of a racist conspiracy. The Seattle whose civic symbol won’t pay workers like Veronica enough to be able to even live in Seattle.

A Ukrainian immigrant and one of 11 children, Veronica lived in Oregon for a while until her family decided to move to Seattle. They thought the city represented a fresh start. Veronica says she remembers seeing the Space Needle on TV and on postcards, and leapt at the opportunity to begin work there last year. To get to her job at the Space Needle, Veronica commutes from Federal Way, a city 30 miles south of Seattle. She sometimes stays with a friend who lives in nearby Belltown when she takes on more hours at the Space Needle. When a semi-truck recently overturned and spilled salmon all over a Seattle highway—causing a debilitating 9-hour traffic jam—Veronica was in the middle of a 12-hour shift at the Space Needle. “Traffic on my commute can be bad, but I’m so glad I wasn’t on the road for that,†she says.

The portion of Veronica’s Facebook testimonial that stuck with me most was the idea of workers “dedicating their lives to the Space Needle.†In a transactional society, the notion of workers getting anything more than a paycheck from a job in the hospitality industry originally seemed sappy to me. But from our seat atop the city in the Space Needle, Veronica breaks it down convincingly: “People don’t work in hospitality for so long at one place because they have no place better to be. They do it for others—because they enjoy helping, and because the job gives them meaning. We have a lot of people who have worked here for 10 years, 15 years, 25 years.â€

Veronica’s emotional investment in the Space Needle was on display in March of 2015 when Local 8 held a rally at the base of the Space Needle. TV camera crews captured her speaking passionately about the Space Needle’s refusal to renegotiate wages with its workers. “People look at you a certain way when you say you’re part of the union, when they see you’re active with it,†Veronica tells me. “But when workers are taken care of, it’s a chain effect: they provide better service, people have a better time, and it’s a cycle of great feelings. Not paying people enough does the reverse.â€

In a tourist venue filled with distractions, Veronica keeps my undivided attention. Her thinking about the labor dispute is sophisticated, but her delivery is devoid of pretention: she believes it’s possible to both “love the Space Needle and ask to get paid better to make that love clear.†As a writer, she makes me think of all the times I’ve ever had an idea but didn’t think highly enough of my own voice to express it as clearly as possible—all the times I ever chose smart-sounding mush over a cleanly-stated phrase that everyone could feel as well as understand. Sitting there, I feel embarrassed that I’m not always able to speak with the same righteous clarity as Veronica. If she had a better paying job that allowed her to finish school, or was born into a world where workers had a more dependable social contract, I find myself thinking she’d make an excellent teacher or politician.

Instead, I can already see signs of a creeping desperation that began affecting me when I was about her age. “Seattle is trying to price out poor people,†she says, plainly. “I keep doing the math to see why I’m saving more and more, but still can’t save enough.†Her inviting demeanor becomes—for a split second—a portrait of despair. In that instant, it dawns on me that Veronica is the future.

During this break in our conversation, I notice an attractive young woman outside in the howling wind who seems to be having a terrible time with life in general. She pulls out a camera phone. I’m alarmed at how quickly her expression transforms into unrestrained glee as she snaps a selfie against the backdrop of Seattle’s majestic skyline, and at how quickly her face defaults back to doom-and-gloom once she puts the camera away. I could write you 1,000 words about how I swear I just saw two different people—but what is a picture worth?

Veronica has a full day of work ahead of her, and I leave her to it. In the elevator on the come down from the Space Needle’s observation deck, I think of a book Fred Moody wrote called Seattle and the Demons of Ambition. And I think of all the ways I’d internalized so many of those demons over the years.

I’m 30 now: posed somewhere between middle-aged stability and the calculated recklessness of my 20s. I think of how the rush to put myself “on the map†when I was a younger man instead put me in insensitive headspaces that I thought winners were supposed to inhabit. I’m a writer and a filmmaker—occupations that require a familiarity with vulnerability that I found extremely difficult to face. I verbally abused coworkers who didn’t see things the way I did, and emotionally abused lovers for the crime of trying to get to know the heart behind my hyperactive brain. In Seattle traffic jams, I drove on the shoulder; in Seattle coffeeshops, I did more talking than I did listening. And I went years without talking to my own parents, as I chased certain accolades with breathless ferocity. Once, I was taken to court when former collaborators on a film I worked on alleged that I owed them tens of thousands of dollars in back wages. I won the case, but I feel like I lost something more important. Maybe the Space Needle can relate.

I saw LeBron in Cleveland and I saw Drake in Toronto, and saw what they were doing as young black men to represent cities with underdog complexes on a national stage. And I wanted that to be me—here, in Seattle. And I still do. But have you ever chased something so aggressively that you ended up chasing it away? I know my best days are ahead of me, and I hope there’s a better way for Seattle, too.

I step off the elevator with my feet on the ground, and my head still in the clouds: I pull my headphones back over my ears, and I cue Nothing Was The Same. I snap a picture of the Space Needle. On the monorail back to downtown, I post that picture to Instagram. I have 206 followers there. I think my Space Needle image is decent. It gets nine likes: one is from an undergrad I mentor who has a parent that was recently diagnosed with cancer. I have plans to visit them in the hospital. Another is from a friend who witnessed her brother get murdered by the Seattle police department when she was a teenager. I owe her a text. Two others are friends who wanted to live in Seattle, but got priced-out and moved. We should get lunch next time they’re in town. The last person to like my picture is my partner. I’d make dinner for her that night. It was delicious, and I regret not taking a picture of it.

On my Space Needle picture, likes from 9,000 or 900 or 90 strangers would be great. But could that take the place of any one of these nine people who I actually know and care about? Some people pay money for spam accounts to artificially inflate their number of followers on Instagram, just so it looks like they’re more popular than they actually are. Nine likes is not a large number at all, but I’m okay with that.

And I guess 206 isn’t that big either. But I’m okay with that, too.

Because I know what a picture is worth.

The answer isn't poetry, but rather language

- Richard Kenney