Essays Sonia Greenfield — March 3, 2014 11:20 — 1 Comment

Playa de Los Muertos – Sonia Greenfield

The couple know at once that this is “it.†They are entranced. – Walker Percy, The Loss of the Creature

I’ve been tracking our visits to Mexico by arranging digital photos along a virtual timeline to figure out what year it was when the country tried to kill me, but it’s all a jumble. We have been there almost every year for the better part of a decade, and the memories have blended into a smear of primary colors and jungle, surf and menace. The reason I can set apart the year we first visited is because we went to the desert part of the country where dusty cacti rise like dilapidated pipe organs. We stayed in Los Bariles, which was on the Baja coast. I remember the smell of a rotting whale polluting the air over the entire string of gringo vacation homes. It was removed from the beach a few days after our arrival, so the stink dissipated. Also, the water in the Gulf of California was just ocean enough to draw good fish for snorkeling – yellow parrot fish mingling with puffers – but also calm enough that we could walk our kayaks in so long as we didn’t mind a little shin and hip bruising from the jostle of small waves against hard plastic.

The event from “the barrels†that shimmers like a mirage is that ATV ride through an arroyo, all white-rock moonscape except for green fronds that rose from the sand and tree roots sent down like long pleading gestures from the upper ledges of the dried-up river. When we rode in far enough, the sand went to mud and we climbed boulders encrusted with wasps’ nests to get close to the tightfisted waterfall. On the way out, you snapped pictures of the arroyo’s entrance, an amphitheater for trickle and flow, while I waited around the bend by a stagnant pool and stared at a dead weasel bobbing at the edge. Riding our ATVs back to the rental place, we passed a pen of goats that sounded like a clutch of babies crying in protest. In this part of Mexico, at least, all the danger appeared symbolic, like photo opportunities waiting to be substantiated: the dead animals, the thirst, the ruined cacti.

At least four of our visits to Mexico have featured a one-night stay in a resort setting, which served as a decompression chamber of sorts. A way to get our bearings. It was, after all, a shock to our Seattle systems, which were so starved for sun they might as well have been subterranean. The Sheraton Bougainvillea in Puerto Vallarta did the trick by providing a pool with swim-up bar, though we never did swim up; tastefully arranged tropical foliage, nothing like the tangle awaiting the wanderer; the requisite buffet featuring ripe mango and hamburguesas; a proper thread count, though I never slept well; and a few strategically placed live lizards for guests to feel like Mexico is wilder than home, yet contained like a terrarium. I suppose some people might just stay in the resort the whole time and venture occasionally into the designated streets of Vallarta to eat the Fodor’s food or shop the Frommer’s shops. To go and make a Kodak moment of the seahorse statue on the malecon. I can’t blame them. On the other hand, we know from experience that even the most controlled attempt at gathering experiences outside of the resort can lead not necessarily to danger, but certainly to short, absurdist plays about the randomness of fate.

Take, for example, that long bus ride we took on the tunel route to the Marina, passing through neighborhoods not designated for tourists’ eyes. There were so many broken bottles embedded in the top of cement walls surrounding domestic compounds that I thought, wow, it’s nice to see that they’re all recycling. But besides that bus trip, the most bizarre moment came in a public rest room in the Mercado Municipal, located along the Rio Cuale. I’m not sure what it was about me that set off the child, and I’m not even sure if I should call her a child. After all, she was dressed like a diminutive hooker: full make-up, cropped top, kitten heels, yet she appeared to be about seven. All I know is that she began speaking to me in a loud and hurried Spanish, and when I looked at her the way anyone looks at someone saying something that he or she can’t understand, she began slapping me. Luckily, she could only reach my belly, and she wasn’t very strong. When she grew tired of hitting me, she hurled more invectives in a language I could understand only on a toddler’s level. Then she paused to gather enough strength to begin hitting me again while I tried to offer her some paper towel because she was too short to reach the dispenser. When she had exhausted her aggression, she left to join her parents in their market stall, which featured a collection of expected merchandise: ceramics with chili peppers, embroidered sombreros, and woven ponchos. Obviously, we didn’t buy anything there. I didn’t know what to do, really, about being assaulted by a child, but I wore an expression of injury-to-insult all the way back to the Bougainvillea.

The year after Los Bariles we stayed in Sayulita, and the trip distinguishes itself as the first one to the Pacific Coast of Mexico, a half-hour north of Vallarta. I suppose it was during this trip that I came to see Mexico as peril cloaked in sunlight. As a land of binary fates. One moment we were enjoying tacos under a palm roof that splayed the sun’s rays like a fan— your beer sweating, the bees dipping their flinty faces into my orange Fanta— the next moment, yards away, a man was declared dead on the beach when the medic tired of pumping his drowned face with a bag. One moment we’re enjoying flan bought from a local woman walking her wares up the street, a few hours later I’m puking into a bucket in the tawdry glow of full moonlight, the ocean sounding as if it were roaring up through the jungle to rip our house from its post. One moment we’re hiking from beach to beach on rocky outcrops, counting hermit crabs in the sandy spots, and the next moment we’re driving past the remains of a pit bull tossed on the side of the highway, its head sticking out of a black plastic bag, ears completely cropped off. One moment you’re riding a wave in like some Greek God born of foam, and the next minute the surf is tearing off my swimsuit and knocking me on my ass.  I never distrusted nature more than here: the bloated termites reaming the wooden mirror in the bathroom; the bats and mice living in the palapa roof, littering our floor with shit; the black, segmented wasps marking the bottom floor of our rented house as already occupied, so keep out.

We ended up in Sayulita because you had spent a week there with an ex ten years prior to our visit, but the town had changed since then. Once a semi-secret cove with a decent break, it had turned into a surfer hangout, and that wouldn’t have been so bad if it weren’t for the pervasive pot culture and sunburned trust-funders taking long pulls from forty-ounce Pacificos well before noon. We just couldn’t handle Sayulita’s new youth culture. I suppose this is how we found San Francisco, or San Pancho, which was twenty minutes north of Sayulita. Just a quick jaunt up highway 200, past crosses marking each curve where an effort to pass on the two-lane road was met with ill-fated consequences and place-markers, past a dead steer on its back with all four hooves sticking straight up into the air. As far as I can tell from my timeline, we have stayed a total of five times in San Pancho: Two times in Casa Melissa before we were married with a child, once in Casa Celestial when our son was an infant, one more time in Casa Melissa’s casita when our son was a toddler (when we had to relocate to Casa Rioja because of a water leak in the main house), and one more time in Casa Melissa when our son was a preschooler. I believe this is an accurate chronology. I have also figured out that it was the 2008 trip to Casa Melissa, several months before our marriage, when I contracted the flu, later turned pneumonia, and it was our most recent trip to Casa Melissa in 2012 when we stayed in that same plague room with the bad painting of a waterfall surrounded by foliage rendered in unreal colors, our son in the next room over, socked in with pillows so he wouldn’t roll off the high bed onto the ceramic tiled floor.

The thing about recalling serious illness is to acknowledge that the recollection is made up of snatches of lucidity pulled from one’s own memory combined with what people tell you about your experience as a sick person. I remember that the sun wiped over that stupid painting in the same way every day I was bedridden, and every night Mars glared at me through the sliding glass door, and he looked livid. I know you pushed me to drink Pedialyte and a syrupy fruit punch I picked out because I thought it would taste like childhood. I know I sat on the shower floor because I was too weak to bathe any other way. I know your Aunt Sue was misophobic and therefore afraid of me. At some point you thought it would be good for me to get out, so I went along on the whale-watching trip, but I was so feverish that the experience exists in my memory like some opium dream of gray humps rising out of silver spray, and me all the while being rocked in my orange life-vest. Then I tried to pass out on the beach and you had to carry me back to the car. According to the photos you took, we saw more whales on that trip than any other excursion before or after. Then when it was time to fly back to Seattle, you had to wheel me though the Vallarta terminals because I couldn’t walk a few yards without collapsing.

We flew home to Seattle in the front row of first class, almost a week into my illness, and my biggest concern was that all the people in the plane within earshot hated me for my wet cough. It was, even compared to future flights travelling alone with our young child, the most interminable flight I have ever been on. Still, I tried to keep my germs to myself, and maybe I managed to do so. We surmise now that it was probably in this metal cylinder, home to a million invisible microbes, where the bacterial pneumonia found its way into my lungs. Does this qualify as irony or reciprocity? Here’s what I recall about coming home: our first trip to the Emergency Room occurred directly after landing, and the driver of our regular car service— whom we affectionately dubbed “The Russian Mafiaâ€â€” actually stuck around the hospital to visit a cousin so that he could take us to our house when it was decided that I had the flu and there was nothing to be done but to hang some bags of IV fluid and send us on our way. I don’t really remember anything about the second trip to the ER except perhaps a flash of hurried movement in a wheelchair, and maybe a very hazy memory of sound: the mechanisms of a CT machine, I think. The way you tell it, I had seemed to be getting better, and we had watched a John Wayne movie in the afternoon. Then you had to go off for work in the very same ER. The following morning when you got home from your night shift, you could hear my breathing from the front door: loud, fast, and shallow. For a little levity, let’s agree that this description reminds us both of at least one of our exes.

The way you describe it, you had to direct me: You need to get out of bed. Put on your slippers, here let me help you. We’re going to get in the car and go back to the hospital. Let me help you up. Don’t worry about getting dressed. No, we’re going this way. Okay, now we’re walking out. I’m going to put you in the car. Let me help you in. Then you tell me that Dr. Copass, the director of the ER, met you on the ramp with a wheelchair and wheeled me in himself. I understand that I was checked into the Intensive Care unit, and that my night nurse was named John, I think. I don’t remember the interim in the ER. I think I remember getting the catheter. The pinch, I mean. I don’t remember the insertion of my feeding tube. I remember the oxygen mask, especially the ocean sound of it. You tell me that I was just strong enough to avoid being put on a ventilator. Good thing I was a runner. I know they checked the oxygenation of my arterial blood so often that both my wrists were purpled with large bruises that showed as a yellow-green fade a week after leaving the hospital. I know my belly was spotted with bruises from my daily Heparin shots to thin my blood. You tell me that I was on Morphine and Valium, and I was given three different antibiotics. I remember Vancomycin. I remember that the liquid food that went through the tube in my nose directly into my stomach made me shit myself because I was too weak to get out of bed, and anyway I was pretty much tied to it with tubes. I know the nurses cleaned me up often, and one time you cleaned me up, too. I know you didn’t sleep. Didn’t shower. Didn’t eat until someone made you. You tell me that the dogs lived in the back of the Land Rover in Harborview’s garage for the week. I laugh now because I remember the cloying smell of the liquid food, and I understand why it was flavored vanilla or strawberry. Not because anyone tastes it, but because someone has to clean it up when it comes out the other end.

Once I began to get better, I joked about my incentive spirometer because I could never remember what it was called. I admit that I had to look it up even now to recall the name. I would call it my aspirational tachometer or my inspirational thermometer or my asphygmemometer. Its purpose was to help me get some lung capacity back. And I did. It took a while, but I did. Once I started to show marked improvement, you showed me my CT scan, pointing out the way the bottom half of my lungs were completely whited-out by sputum. When I left the hospital, I was fifteen pounds down from when we left for Mexico weeks earlier, but it wasn’t a flattering weight loss. Weighing in at one-twenty, I looked skinny-fat. I remember when the old battle-ax of a nurse asked you to leave so she could bathe me and braid my hair. How afterward I looked like one of those paintings of children with abnormally large eyes. By the way, have I told you that you were heroic? Can I say thanks again for that requested Happy Meal, which had been my first real solid food in weeks? Things were getting better when we made that big outing afterwards to Fred Meyer, even if I had to grip the shopping cart like a walker. Speaking of walkers, I have since learned that pneumonia is sometimes called “the old person’s friend†because it often works as a mercy killer.

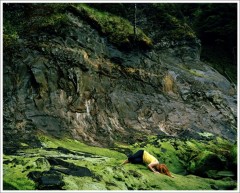

I want to pivot back to Mexico: After all, we keep returning. The last time we were there, we found that sweet little beach on Punta de Mita and set up our tent so our son could nap in the sand. The waves there were so uniform and slow-curling I could almost imagine our child playing in them. We can’t blame Mexico for my body’s failing any more than we could attribute my return to health to Seattle’s climate. We know how absurd that is. However, the question that keeps recurring is whether the nature of the country is benevolent, malevolent, or merely neutral. Let’s review the collection of odd images and experiences that have yet to be symbolized: the dead sea turtle that looked like a rusted-out Volkswagen floating near our boat; the hundreds of small bats that emerge all at once from the roof of Casa Melissa’s when dusk tips over into night; the pile of fish carcasses, glutted with flies, a few steps away from Playa de Los Muertos; all the cemeteries of cinderblock and colorful plastic flowers climbing up the hills; the al pastor from the place with the plastic chairs and the twenty-seven mosquito bites I acquired on my ankles while eating four of the best fucking tacos I have ever had; the tiny, perfect scorpion shaken from the patio chair, almost adorable because of its size. The monkey and dog sharing the same cage at the beach restaurant with the dubious shrimp. It may be that although the symbols appear extreme, their intent is neutral. Nevertheless, Mexico understands, as do I, that the subject of death is not an easy one to avoid.

One Comment

Leave a Reply to Sasha Eakle Sanchez

The answer isn't poetry, but rather language

- Richard Kenney

Beautiful Sonia!

Extraordinary mix of the gorgeous and the strange.